Sariev Contemporary highlighted in New York Times article about Plovdiv

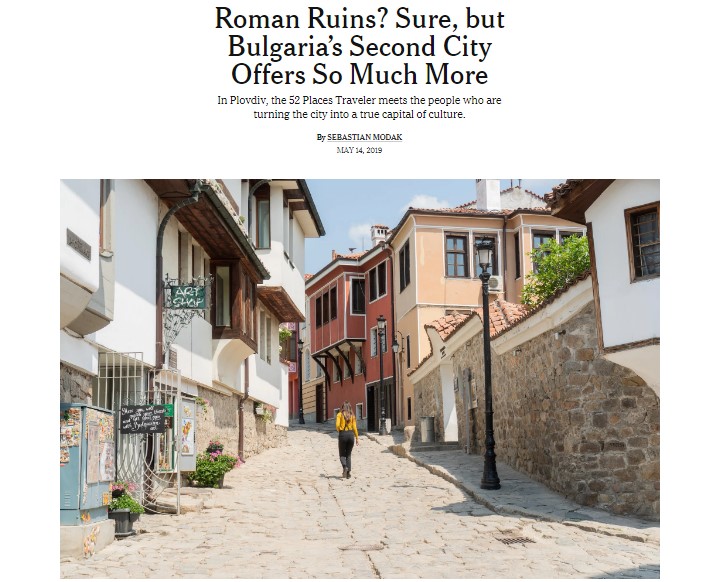

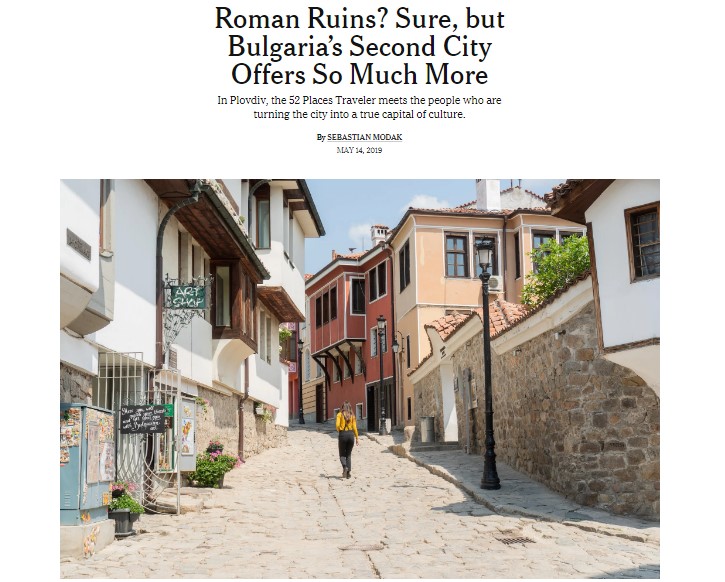

Sariev Contemporary has been featured in New York Times recent publication about Plovdiv and the people who are turning the city into a true capital of culture. In the article called "Roman Ruins? Sure, but Bulgaria’s Second City Offers So Much More" , its author Sebastian Modak, New York Times' 2019 52 Places Traveler, highlights some of Plovdiv's most prominent art events, institutions and the figures behind them.

Among the people whom he met are Sariev Contemporary's founders Vesselina and Katrin Sarievi, who also talked about some of the projects that they have started, and introduced him to the gallery's represented artist Martina Vacheva:

"It took me a few days to realize that Plovdiv is not a place built around tourism, but rather a booming city whose appeal to travelers can and should extend beyond the historical allure that attracts so many. Bulgaria’s second city is a place of layers, where a new breed of artists, entrepreneurs and community leaders are just as concerned with the city’s future as they are with its past.

SARIEV GALLERY Contemporary is a gallery just off Plovdiv’s main street, past the office of the OPEN ARTS Foundation and the bohemian hangout, artnewscafe. A 180-square-foot white box, it is easy to miss. But the gallery is the heartbeat of Plovdiv’s contemporary art scene, and over the last decade, its proprietors — Katrin Sarieva and her daughter, Vesselina Sarieva , who also run the cafe and the foundation — have created an ecosystem that combines the arts, community organizing and historical preservation. More than one person I met credited them with bringing contemporary art to the fore, not just in Plovdiv, but in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe as a whole.

Vesselina has taken Bulgarian exhibitions to art shows all over the world, and works with young up-and-coming artists and big name collectors alike.

Vesselina has taken Bulgarian exhibitions to art shows all over the world, and works with young up-and-coming artists and big name collectors alike. The event the Sarievas are best known for, though, is НОЩ Пловдив / NIGHT Plovdiv, held every September for the past 10 years, when the city’s galleries, museums, bars and historical sites stay open after hours and host events that span the artistic spectrum.

“Before we started the Night, the idea of culture here was very narrow,” Vesselina said. “You had high culture — the museums, the opera — and then everything else was ‘low culture.’ People thought galleries were just shops for art.”

Without the work of the Sarievas, it’s hard to say whether the conditions for a “capital of culture” would have been realized at all

On a sunny day, Vesselina took me for a long walk to hit some of the destinations on the Alternative Map of Plovdiv, a project started by Katrin Sarieva, who doubles as the city’s unofficial historian. A concerted effort to show tourists and residents the attractions that exist outside of the usual tourist routes, the map offers a fascinating look at a city with many facets and a story of survival.

We walked through the Hadji Hassan Quarter, tucked next to the Old Town, where many of the city’s Romani residents, sometimes referred to as Gypsies, live. There, in hastily built homes with the occasional horse cart parked out front, they’ve preserved their language and customs even after decades of tradition-crushing communism. One woman smiled at us as she washed clothes using an ibrik, a Turkish pitcher which, as Vesselina described it, is “the kind of thing you usually see in the Ethnographic Museum.”

We passed the remnants of Bulgaria’s communist years, the Brutalist Central Post Office and National Library. On this part of my tour, too, there were stories of perseverance. One building, the Cosmos Cinema, is an abandoned movie theater built in the 1960s. About 10 years ago, it was almost destroyed to make way for a shopping mall. It was Vesselina and others in the artistic community who rallied around the cause to stop the city from doing it. Its future is still uncertain, but it won’t be turned into a pile of rubble.

Vesselina introduced me to Martina Vacheva 31, one of the most promising young artists she works with. Together, we walked around the neighborhood where Ms. Vacheva was raised. Trakia, a city within a city, is a seemingly never-ending collection of massive Communist-era apartment blocks, 50-year-old paint peeling off soot-stained walls.

Ms. Vacheva was discovered by Vesselina when she was creating fanzines for “Baywatch,” “Twin Peaks” and (seriously) “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman” — some of the first American TV shows to come to post-Communist Bulgaria. In her work, Ms. Vacheva marries the grandness of history with absurd elements from the present day. In a recent series of ceramics, for example, she takes inspiration from Thracian works discovered in Plovdiv and, using traditional techniques, imbues them with modern motifs: A beer bottle is included in a scene of ancient revelry, a boombox is placed in the back of a donkey cart…."