Stories is a conception initialized by Sarieva Gallery and aimed at forming an environment of dialogue and communication between authors and audiences through various curious formats and media. Stories poses questions, seeks answers, provokes and experiments by inciting a more personal relation with the art creators themselves.

The curator Vesselina Sarieva initiated a series of interviews with authors Vladimir Ivanov, Stanka Tsonkova – Usha and Sophia Grancharova within the context of their collaborative show ECHO. The shared memories and the short documentary footage allow us to peek into the ethos of the young author – then and now.

Find more information about the exhibition Echo here.

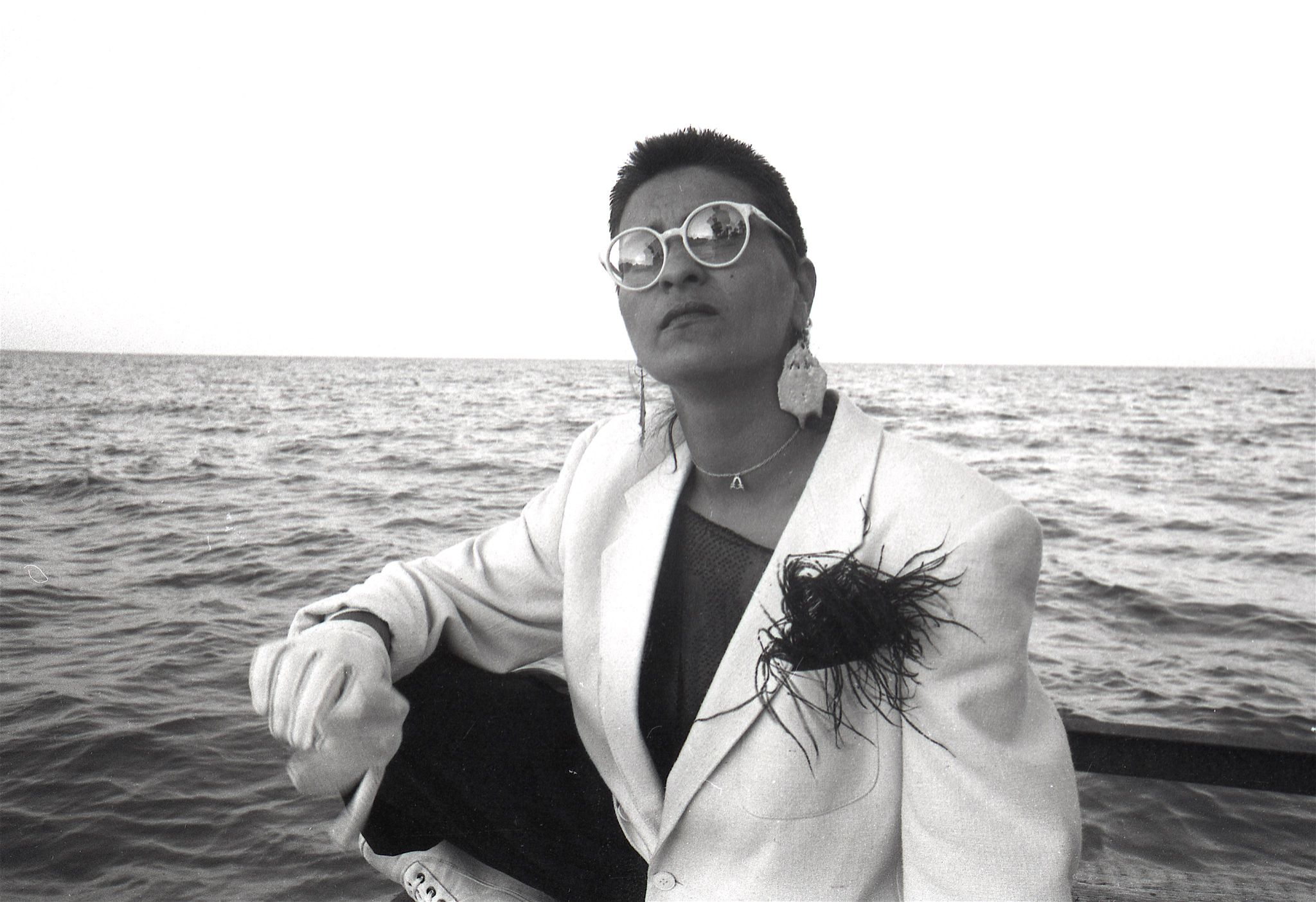

Stanka Tsonkova - Usha

S: How would you describe the time in which you lived and created the artworks of the exhibition ECHO?

The past bears within itself two types of truth – objective and personal. Without any doubt, my generation lived through the most productive part of their lives during the socialist regime with all the ensuing consequences.

Whereas the personal assessment is strictly individual and related to one’s choices. It is about whether one remained true to oneself and the chosen path, or chose the opportunity of being privileged and taking advantage of the possibilities offered by the system: decent education, a job, material gains – all the seductions the conscience is tempted to compromise itself with. A time of decisions and choices whose echo resounds to this day – those who were well-established back then are still successful as we speak.

While those who never lost themselves didn’t sell their souls and still struggle for a place of their own, for recognition and non-forgetfulness. The echo of the past is a rediscovery of past experience and its interpretation by the new generation in the present. “We must take from the past the fire, not the ashes.” (Jean Jaurès).

S: Who was the young artist Usha back then?

Usha back then: curious about people and the world, emotional and outspoken, with all the ensuing painful injuries; trustful and stupidly naïve, artistic and free in spirit, disregarded and resisting, an ultimate outsider – SURVIVING at the cost of her life!

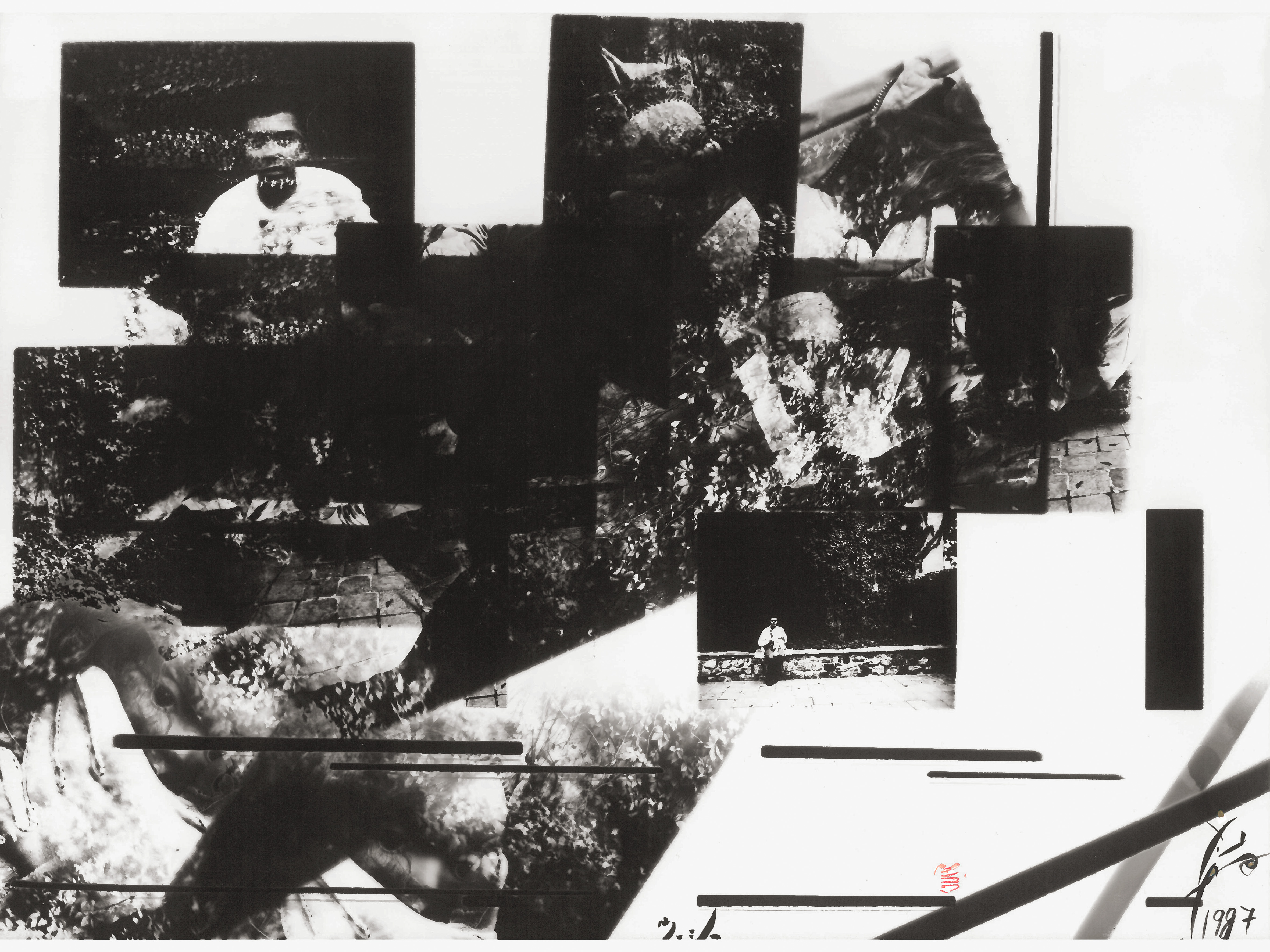

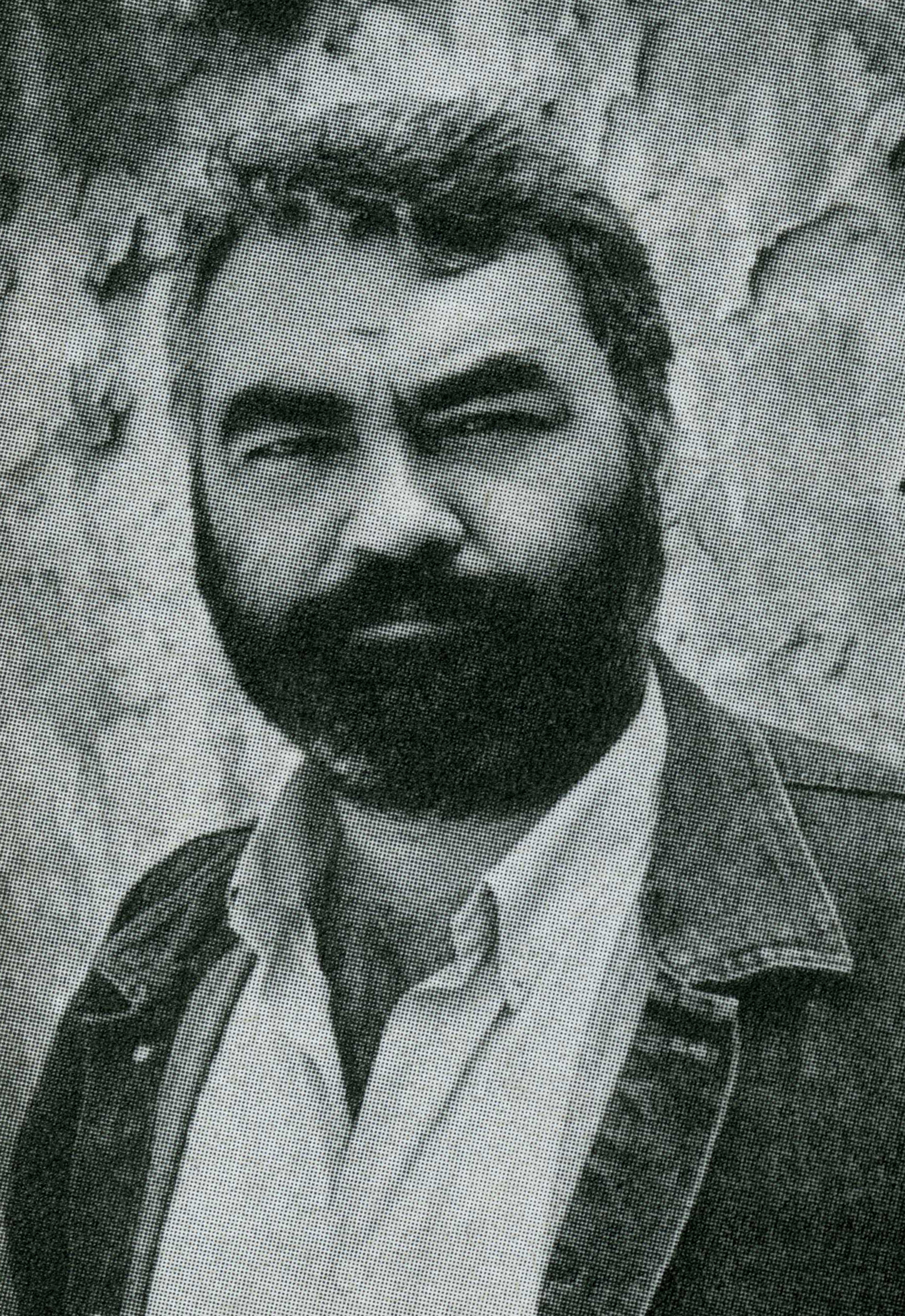

Vladimir Ivanov

S: Who was the young artist Vladimir Ivanov back then?

Young and assertive. My academy was not the Academy, but the Academy library, the French Philology library in Sofia University, the library of the French Cultural Institute, reading room 4 of the National Library and the library of the Institute of Art History. I was reading the magazines Studio International, Kunstforum International, Opus and Artforum, to which I’ve been subscribed to this day. Those were my universities. In 1974, I went to see the biennials of graphic art and poster design in Kraków and Warsaw.

I showed two of them at the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Varna in 1981. The same year, the exhibition The Artist at Work in America, featuring works by Rauschenberg, Jones, Warhol and others, was shown in Varna. It was a feast.

This was my maturation – economic, political and spiritual. I witnessed, although from afar, the 1968 events in France, Germany and Italy, the Vietnam War and the protests against it in the USA. On the BBC, I listened to Georgi Markov’s In Absentia Reports and Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Meanwhile, I read Orwell’s 1984.

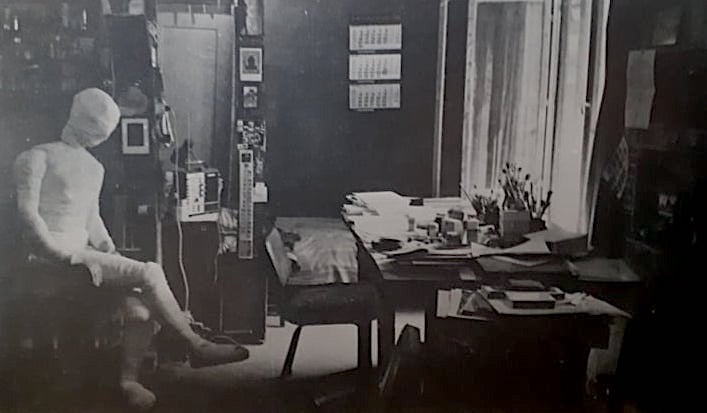

During the 1980s, I continued my work in the sphere of visual arts, independent of the Union of Bulgarian Artists as ever. I stayed at my “Vulcan” studio in Varna from 1981 to 2006. It was a nice beehive for artists. Yet, “Vulcan” was different from what was known about it as a myth. There were different artists – such that advocated “moderate progress within the law” and others who worked against the law. On the photos, you can see me and my studio in “Vulcan”, along with part of my installation ECHO.

S: How would you describe the time in which you lived and created the artworks of the exhibition ECHO?

I wanted Bulgarian art to be emancipated in relation to the rest of the world and for me to be a contemporary artist without any domestic troubles. All my efforts were directed towards this goal. This took me to the Netherlands in 1990. A very productive period, during which I staged 10 exhibitions.

In 1994, I returned to Varna.

In 1996, I was co-founder of VAR(T)NA Club.

In 2002, I staged a large exhibition in Sofia City Art Gallery, it was actually my professorship. In the meantime, I lectured at the Varna Free University. Gradually, I realized that the old system was still setting the rules, that history was being counterfeited, and my life was part of this. Things became really complicated, not just locally. Yet, I persist in thinking that my works shown at the ECHO exhibition in Sarieva Gallery are like the early swallows of Bulgarian contemporary art.

In 1975, I left the Academy and went on an internship in Dresden where I got acquainted with Beuys’s work in many of the city galleries. Some colleagues of mine gave me the address of a private underground gallery located in an apartment in Berlin that I went to visit. In 1976, I went to Weimar to attend more discussions on Beuys. In 1979, I went to Paris at the invitation of a French friend of mine. It was a great opportunity for me to visit the Louvre, the Centre Pompidou, as well as numerous Parisian galleries. All this boosted my ambitions to devote myself to conceptual art in Bulgaria. I started making “fantastic landscapes” that were actually conceptual artworks, but back then in Bulgaria there was no one to assess them as such.

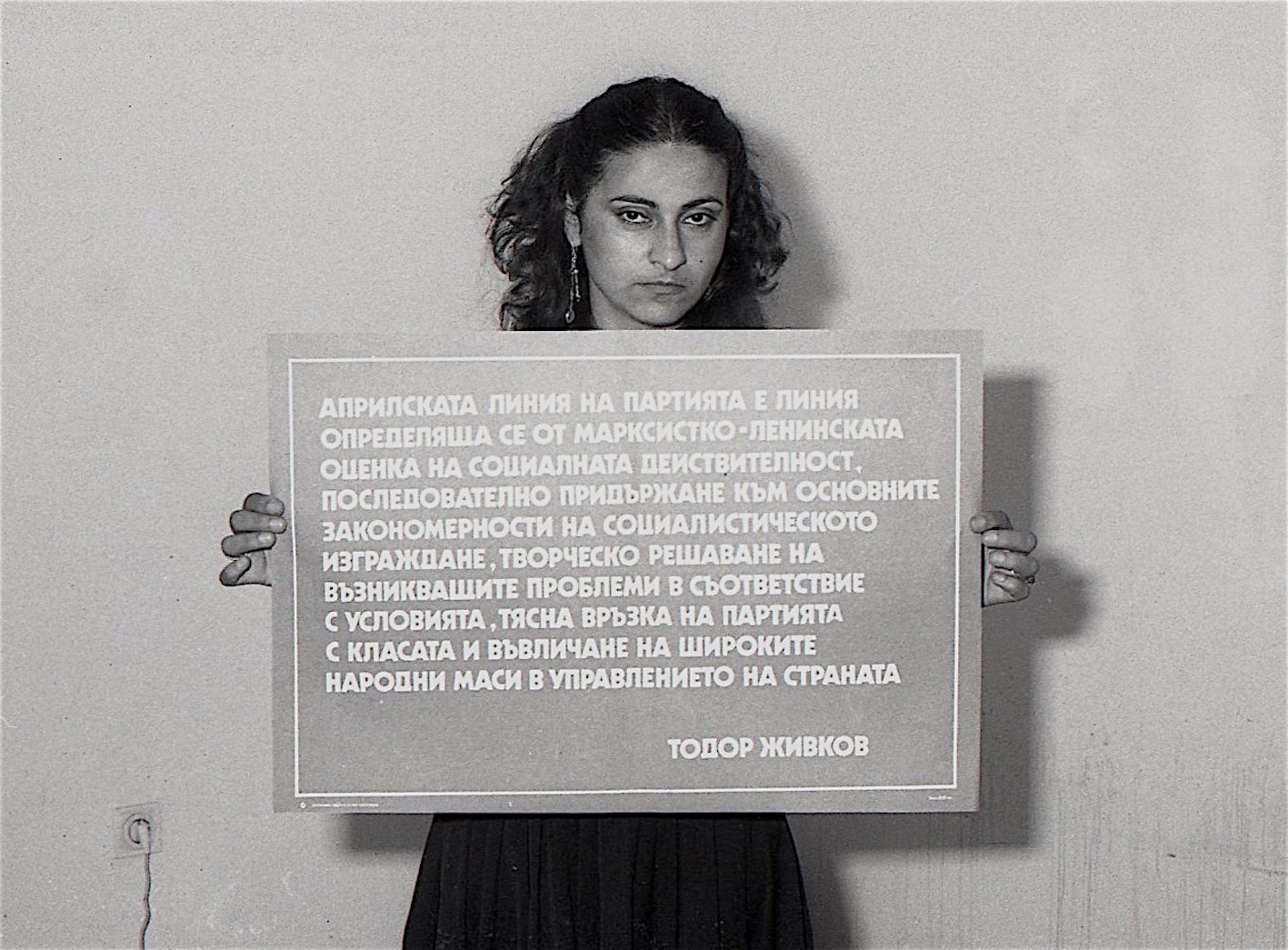

Sophia Grancharova

S: Who is the young artist Sophia Grancharova?

Sophia Grancharova is someone who believes in dialogue, in chance encounters, combinations and symbioses, in the endeavour of gaining knowledge and understanding of the other side. Hence, I believe, the interest in the places and means we use to communicate with one another, making sense of and shaping the present together.

S: How would you describe the time in which you create your artworks today?

It is naturally much more difficult to make a statement on the present than when you speak from the distance of time. My emotional nature compels me to be forever optimistic about the present and the future. At the same time, reason whispers to me the sensation of a certain cyclicity and recurrence to the point of fatigue. You can see – for as long as I can remember, I know we are in crisis: political crisis, economic crisis, value crisis and so on, and so on. Therefore, I wonder whether we can break this cycle or at least alter it. Maybe not, yet I think it is important to do the best we can while we are inside the eye of the storm.