Artan Hajrullahu / Dimitar Solakov / Jelko Terziev / Krassimir Terziev / Luchezar Boyadjiev / Mina Minov / Pravdoliub Ivanov / Samuil Stoyanov / Sasho Violetov / Tekla Aleksieva / Valio Tchenkov / Viktor Petrov

13 December 2025 – 1 March 2026

Artan Hajrullahu / Dimitar Solakov / Jelko Terziev / Krassimir Terziev / Luchezar Boyadjiev / Mina Minov / Pravdoliub Ivanov / Samuil Stoyanov / Sasho Violetov / Tekla Aleksieva / Valio Tchenkov / Viktor Petrov

13 December 2025 – 1 March 2026

Sarievа/Gallery, Plovdiv is pleased to present the group exhibition “snowball”, featuring works by Tekla Aleksieva, Luchezar Boyadjiev, Artan Hajruhllahu, Pravdoliub Ivanov, Mina Minov, Viktor Petrov, Dimitar Solakov, Samuil Stoyanov, Valio Tchenkov, Jelko Terziev, Krassimir Terziev and Sasho Violetov. The exhibition will be open to the public from December 2025 to March 2026 and presents a wide range of painting, drawing, objects and installations – some never shown before – created between 1986 and 2025.

“snowball” is more a snowball fight than a traditional exhibition – each artwork aims at another, sometimes hitting, sometimes missing, with the rules of the game never fully clear. Sarieva / Gallery invites visitors to step into the center of this skirmish and observe as if they themselves are taking part in it.

Somewhere near the end of the exhibition’s preparation, just before its announcement, stands a roughly 50-second, 35mm silent film by the Lumière brothers, “Bataille de boules de neige” (1896). The film is not among their most recognizable cinematographic attempts and is part of their catalogue of over 1,400 titles. Shot on a street in Lyon, France, it depicts a lively winter scene: a group of men and women throwing snowballs, their movement appearing both spontaneous and theatrical, with many participants looking directly into the camera – a hallmark of a time when the operator was part of the event. At one moment a cyclist crosses the scene, only to be struck by snowballs; he loses balance, falls, and loses or forgets his hat in the middle of the battlefield – a comical, almost slapstick moment expressing joy, movement and immediacy that remain vivid today.

In the middle of the street, among and with the participation of everyday townspeople, the chaos of the game unfolds. When does this chaos begin to form a narrative, and is that even possible? It is precisely this cinematographic potential of such dynamics that the curators aim to create. Many of the works in the exhibition discover potential in ordinary, everyday situations and domestic elements—seeking to suggest: How can we live more playfully? And what, after all, is the purpose of art?

The work on the exhibition began as a tossing – and at times throwing – of snowballs: artworks that gallerist Veselina Sariеva and collector Simeon Markov exchanged in an ongoing visual chat. Veselina shared works united around ideas of reversal, paradox, play, comic sensibility, collisions of high and low culture, nature and technology. Simeon continued the thread with staged relationships, the multiplication and disintegration of familiar symbols, absurdity and citationality.

The two moved through potential titles such as “Paradox”, “Oxymoron”, “The Nature of Things”, “The Sum of All Hopes” (a paraphrase of the title of one of the two works by Luchezar Boyadjiev shown in the exhibition), until finally, in a light and playful discussion over coffee and cake, they “stole” the name “Snowball” from the eponymous work by Mina Minov – a minimalist and poetic sculptural gesture: a snowball wrapped in transparent tape. The English word articulates the concept: a single word for a game, an action, and a visual experience.

Connections between the works are visual, conceptual or associative, sometimes seemingly absent, leaving empty spaces for the viewer to fill with allegories alternative to any grand narrative. These may be fleeting or disintegrating, and precisely through that they stimulate over-interpretation and reflection.

Pravdoliub Ivanov’s frontally positioned “Endarkenment" (2007–2015) plays with the word (and idea of) “enlightenment” by presenting a flashlight that, instead of illuminating, casts a shadow.

In “f(o)xy” (2024), Viktor Petrov seems to transform the ancient Thracian triskelion into an object made of three fox tails of synthetic fur, twisted into a knot without beginning or end. The artist explains that the title plays with the form of a mathematical function: just as variables x, y and z define the three spatial axes, o refers to the “origin” – the point from which everything unfolds and into which everything dissolves. The fox, as a mythical figure, enters into playful contrast with this geometric system. Known for its cunning and its ability to “bend” the truth, it acts like a function that destabilizes the rules of visual perception.

This visual logic of interweaving continues in Sasho Violetov’s painting (“Untitled”, 2025). Of his practice he notes: “I often work with familiar archetypes and cultural symbols only to reimagine them in unfamiliar, even uncomfortable contexts. Images, phrases and gestures taken from everyday life, memory and popular culture intertwine in compositions that imitate logic yet reject answers.”

Valio Tchenkov engages with contradiction in his “Prey in a Good Mood” (2025), attempting to shift perceptions of violence, prey and victimhood, while treating his peculiar characters and the emerging story between them with a particular visual care.

“The Message Is Not the Media II” (2000) by Jelko Terziev challenges the boundaries of language and the visual – that is, meaning itself – in a situation where word and image become incompatible: twenty-three images painted in oil and acrylic reproduce an episode from a popular Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge comic. The visual narrative begins with a witch releasing an evil spirit, triggering a conflict between the two main characters. At the end Uncle Scrooge is devastated to find his treasure vault empty. The dialogues from the original story are replaced with textual fragments from José Ortega y Gasset’s “Essays”, placed in the genre’s customary speech bubbles.

In the ironic “Portrait” (2016), Krassimir Terziev depicts a bear against a green background commonly used in film and television to be keyed out and replaced or to facilitate special effects. The same color (or a memory of it) appears in Artan Hajruhllahu’s “Memories on the Hill” (c. 2021), beyond its conceptual function in Terziev’s work. In his typical naïve style Hajruhllahu illustrates a silent conversation between a person and a memory hovering somewhere far off on the horizon of consciousness. His other work “Ball” (2018) shows a boy in a bare winter landscape whose ball has “escaped” high up onto a branch.

Samuil Stoyanov is presented with two works. “A Call” (2010) presents a brief, almost absurd dialogue, stripped of context and characters. The exchange – “Hi, how are you?” / “I can’t tell you over the phone.” – ironizes social clichés by exposing the gap between a formal gesture and an actual state of being, between what we say and what we withhold in a condition of silent anxiety. The work “Mirror” (2017) imitates a mirror, yet it is painted as if hastily, with silver spray directly onto the wall, echoing our desire to see ourselves right now and also precisely here. Thus the two works – one based on language, the other on image – create a shared field of doubt, reflection, and a gently ironic tension between the visible and the invisible, between what is spoken and what is left unsaid.

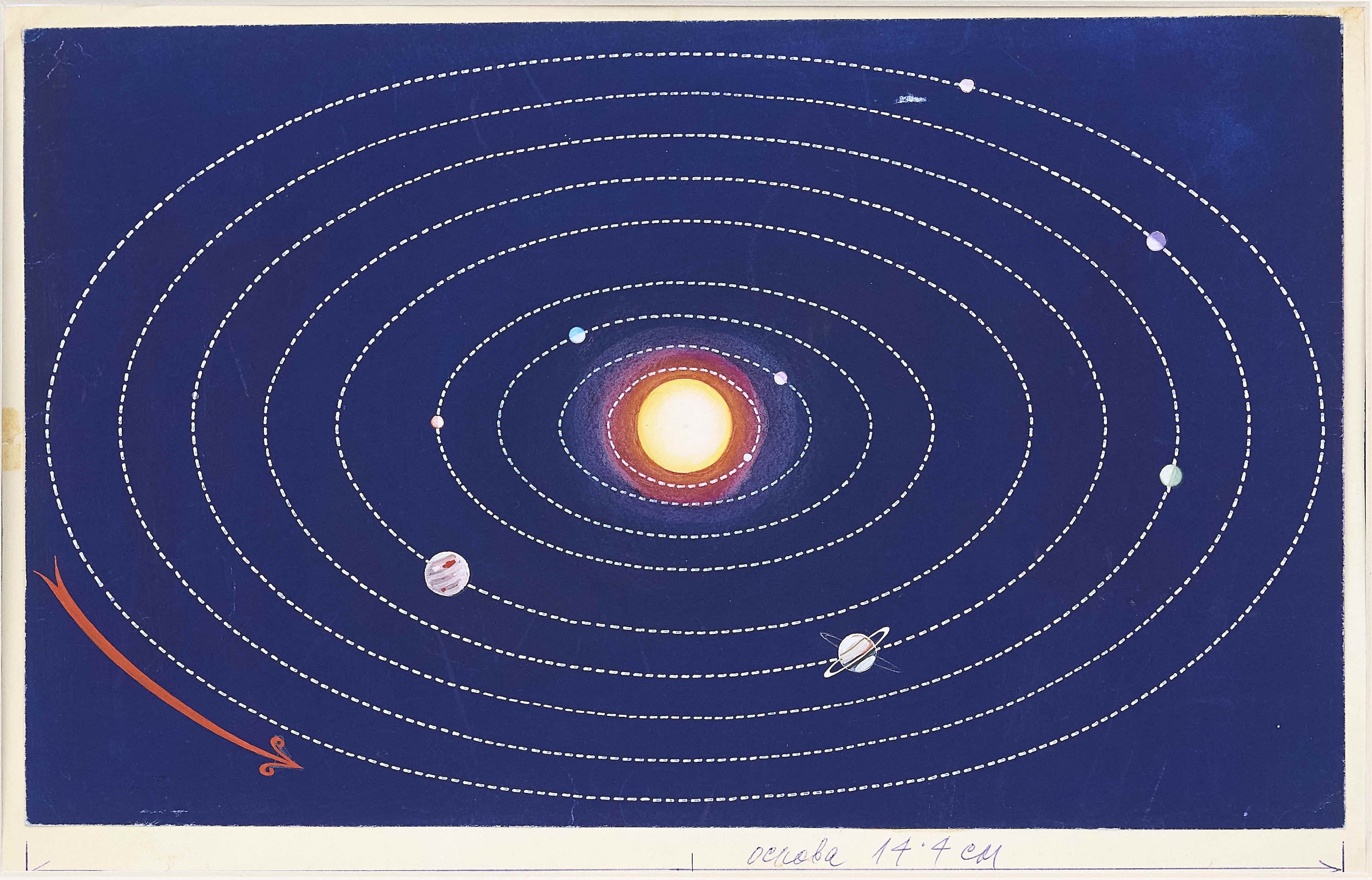

Tekla Aleksieva’s “Dusty” (1986) is the original drawing for the cover of the eponymous book by Australian writer and animalist Frank Dalby Davison, which tells the story of a dog, a cross between a dingo and a kelpie, struggling with its wild instincts. “Solar System” (c. 1980s) – typical of Aleksieva’s educational illustrations – was created for textbooks and teaching materials. We see a skillful interweaving of scientific information and artistic vision: the arrow is drawn like something out of a fairy tale; it shows planetary motion and carries a speculative, even conspiratorial tone. There is a playful tension between fact and artistic interpretation, between science and imagination, turning the system not merely into a learning aid but into a visual experience that sparks curiosity.

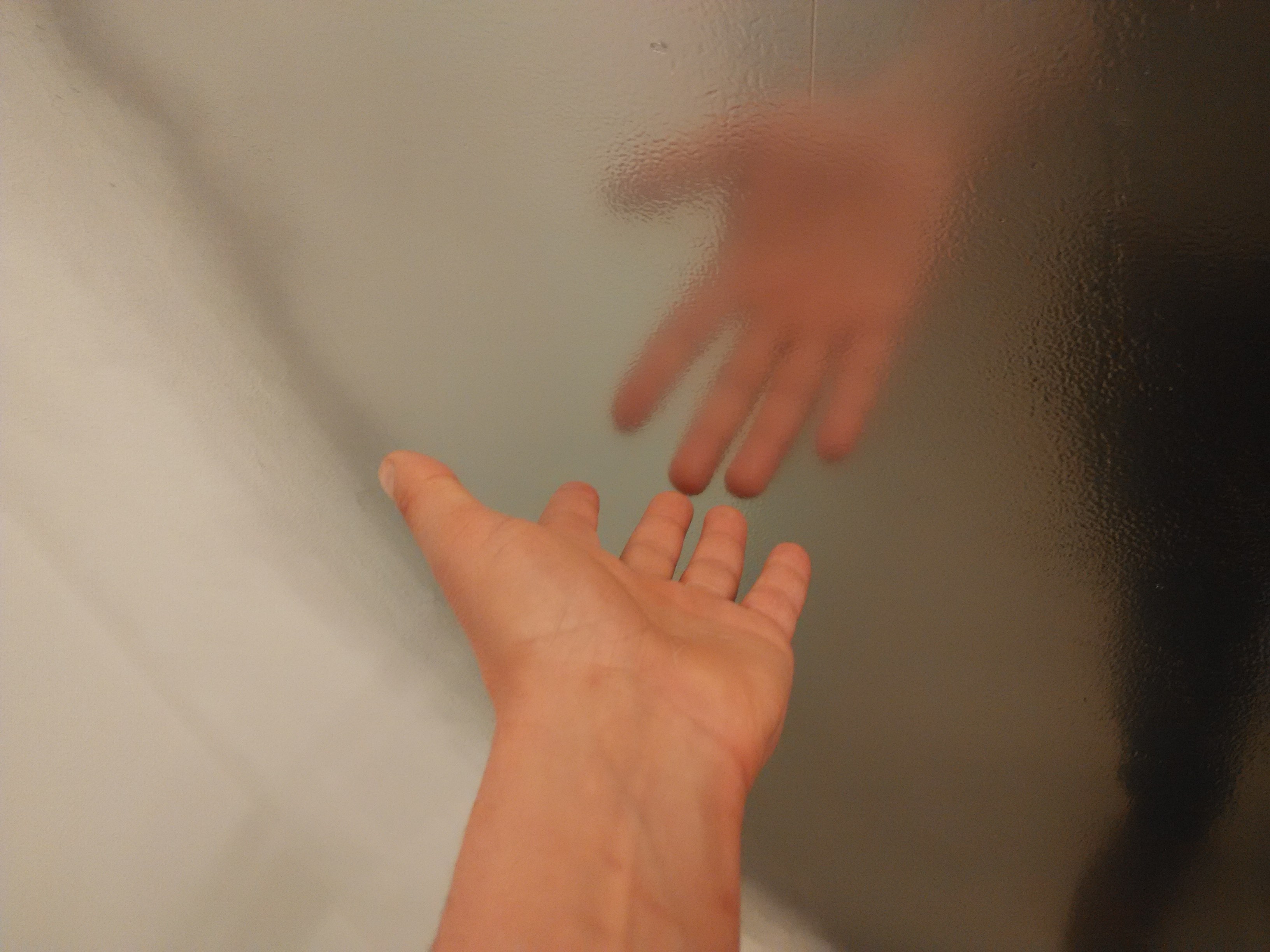

Dimitar Solakov’s installation “Keep Calm And Carry On” (2024) shows two human figures, presumably a man and a woman, under a blanket – only their legs visible. Through a combination of household objects, mechanics and electronics, Solakov creates a scene oscillating between intimacy and absurdity, comfort and discomfort, the everyday and an unexpected dynamic, positioning the viewer as an involuntary voyeur – watching with unease, yet with sweetness.

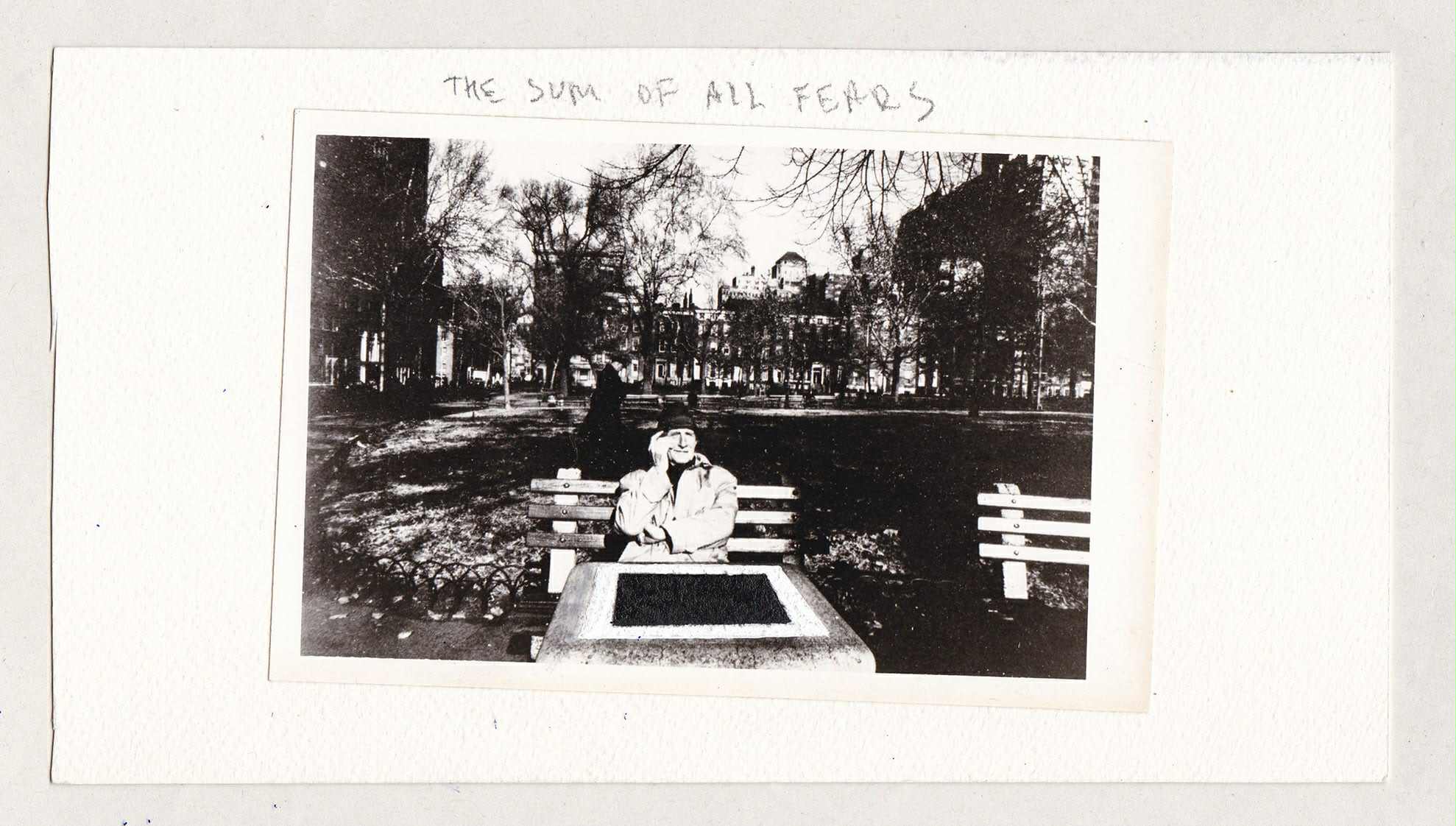

The exhibition includes two works by Luchezar Boyadjiev. The previously mentioned drawing titled after Tom Clancy’s well-known spy thriller “The Sum of All Fears” (2012), in which Marcel Duchamp sits before a black square instead of a chessboard, connecting the notion of the “black square” in painting with the idea of the “endspiel” in chess. The drawing visualizes the moment when an ending becomes a new beginning, touching on fears associated with the end – of art, of the world, of life, of the author. He also presents a new version of his legendary work “Intimate Endspiel (a domestic version of “Endspiel: The Good, the Bad and the Lonely”, 2012)” (2018–2025). Also inspired by Duchamp – who, at the end of his life, wrote a book on the final phase of the chess game – the work enables and anticipates a game without time limits. The message is clear: art has no end; there will always be someone who wants to play and participate, and someone who wants to watch the game.

At the end of a lecture he gave in 2020, Boyadjiev noted: “When I have answers – I give lectures. When I have questions – I make artworks.” Taking this quote backwards, inverting it, we ask: if the exhibition’s works are answers, are they not answers to the same question? And must we know what that question is for the game to go on? A game of lightness and effort, of violence and delight, of joy and rivalry. A snowball fight.

_

Media Covarage

Artviewer, snowball at Sarieva, Plovidv, January 20, 2026

Meer: Snowball, 13 Dec 2025 — 1 Mar 2026 at the Sarieva/Gallery in Sofia, Bulgaria, 27 January 2026

Tekla Aleksieva

Dusty, 1986

Original drawing for the cover of the book “Dusty” by Franc Davison, Eco series, Publishing House “Zemizdat”, Sofia

Tekla Aleksieva

Dusty, 1986

Original drawing for the cover of the book “Dusty” by Franc Davison, Eco series, Publishing House “Zemizdat”, Sofia Viktor Petrov

f(o)xy, 2024

object

Viktor Petrov

f(o)xy, 2024

object Dimitar Solakov

Keep Calm And Carry On, 2024

installation

Dimitar Solakov

Keep Calm And Carry On, 2024

installation Samuil Stoyanov

Mirror, 2017

silver spray

Samuil Stoyanov

Mirror, 2017

silver spray Mina Minov

Snowball, 2012

object

Mina Minov

Snowball, 2012

object Tekla Aleksieva

Solar system, 80s

illustration

Tekla Aleksieva

Solar system, 80s

illustration Luchezar Boyadjiev

The Sum of All Fears, 2012

drawing on photography, pasted on watercolor paper

Luchezar Boyadjiev

The Sum of All Fears, 2012

drawing on photography, pasted on watercolor paper Sasho Violetov

Untitled, 2025

oil on canvas

Sasho Violetov

Untitled, 2025

oil on canvas